Since its launch on Christmas Day in 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope has exceeded all expectation. We’ve seen new things and old things, and new images of old things, and all of this information has excited me to no end as a normal, my-brain-just-barely-understands-this stuff kind of person, which means that it must be beyond exciting for people out there who actually know—or at least have a better idea—of what all of this entails.

What must that be like, I wonder—to operate in a field as vast and unknowable as the stars? Or more precisely—what must it be like to formulate hypotheses about the unknowable above us, and then see them confirmed or stretched or done away with altogether as new information comes to light?

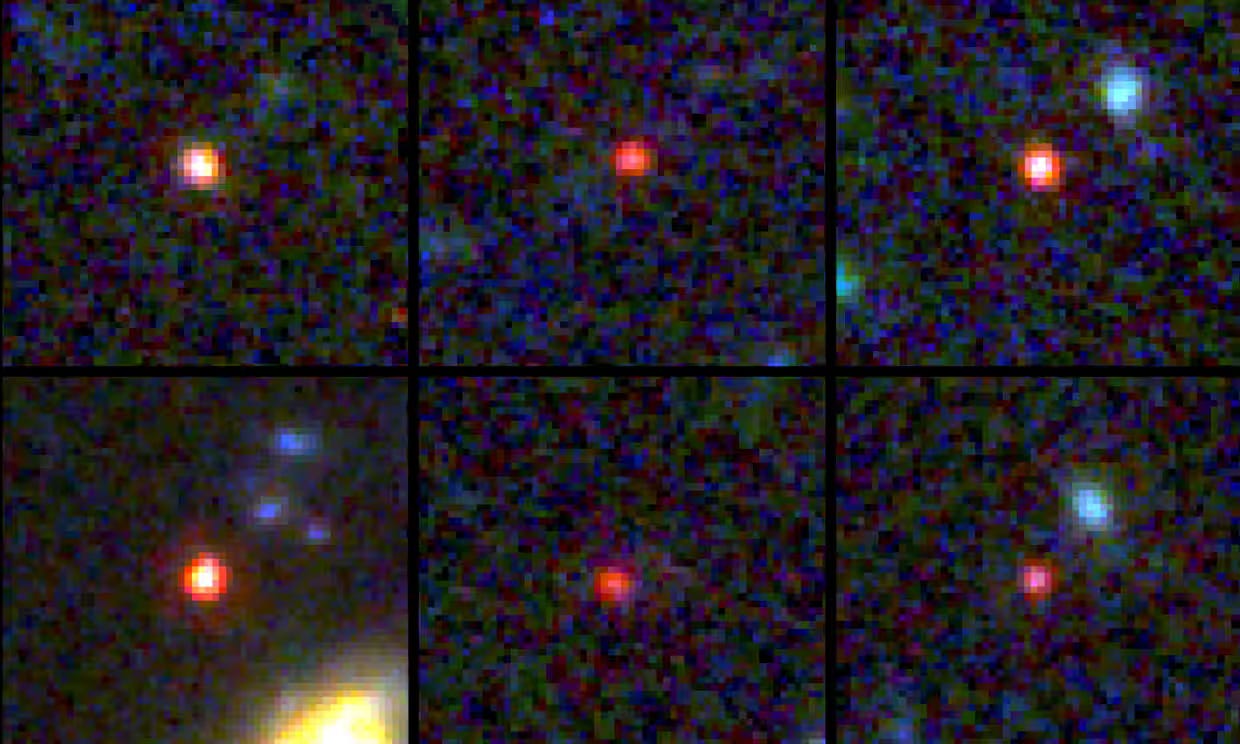

When I was on the Isle of Coll last month, one of the things the facilitators talked about was the fact that the early years of the universe—the first billion or so—were too volatile to allow for the formation of galaxies. In her wonderful book First Light: Switching on Stars at The Dawn of Time, the astrophysicist Dr. Emma Chapman explores this period of time. And yet, even now, the JWST is offering up images of things that show us other possibilities. Galaxies that look to have formed a mere 300 to 500 million years after the Big Bang, during a time when this was deemed impossible. Galaxies whose very existence has led to some astrophysicists nicknaming them “universe-breakers”, because their size and maturity so soon after the Big Bang calls into question so much of what we understand about how the universe works.

You think the world works one way, and then one day new information comes in and everything you thought you knew is blown to bits. This, it seems to me, is what being human in the world is all about. And we can choose to be frightened of it—to cling to what we think we know in the face of all of these vast unknowns—or we can let go, and stand under the vastness of the sky, one small and insignificant and also enormous part of the mystery.

During my last two weeks in Scotland, I did a lot of travelling. Went to Inverness for a couple of days and walked along the River Ness, saw live music, spent time with the trees on the Ness Islands. Then I took a bus tour up the northeastern coast to John O’ Groats, the most northerly settlement on Great Britain, and from there to Dunnet Head, the most northerly point on the mainland. From there, I went back down to Glasgow and Edinburgh and hopped on a bus tour up to the Isle of Skye which took us through the Highlands, golden and splendid in late autumn. And then, after Skye was over, I spent my last few days in Scotland traveling back to Edinburgh and other towns along the coast, seeing old friends and catching up with as many people as I could before I had to leave.

It was beautiful and glorious and also very tiring. I deperately wanted to get my Sunday Letters in those last two weeks out on schedule but each night I’d come home from a day of adventuring and practically fall into bed. And so the Sunday Letters went unwritten, and then I got a cold, and the nostalgia of being in Scotland and the joy of being in Skye and Inverness mingled with the pang of soon having to leave so that there was always so much feeling rumbling around in my gut I wasn’t quite sure I’d be able to put words to it.

Then, when I was coming back from Inverness, I found out that the partner of an acquaintance had died, suddenly and unexpectedly. And only a few short days after that, a friend reached out on Instagram to say that their father had also died. Suddenly. Unexpectedly. One moment there and the next moment gone.

You think the world works one way. You think you understand it, in at least some of its glory and wonder. And then, one day, death comes like a hammer, and everything in the universe breaks and you are left spinning in the dark, wondering how gravity will ever pull you back together.

As my time in Scotland drew to a close I found myself waking up at that delightful old time of 3amish again, buzzing with lactic acid and stress. The trip was winding down and now, looming ahead of me, the winter of writing sat enormous and terrifying.

Who am I, really, to write about the stars? I know nothing about the cosmos. I know what I can glean from NASA press releases, from documentaries and books. I went to a stargazing weekend on a tiny little island off the coast of Scotland that houses, at its max, two hundred people. The facilitators explained the theory of relativity in simple terms a child could get and still I understood hardly any of it. I have barely scratched the surface. I love the night sky with a child’s love—a fierce, reverberating love that just is, and understands barely anything.

And who am I, really, to write about grief? How do we, how can we, put words to something so insidious and shifting, so monstrous and also so mundane? I woke up those mornings and vibrated with the anxiety of it. And in between those mornings I took the train to Inverness and Glasgow and Edinburgh and all of those other places and I thought of this woman whose partner had died, this fellow writer I don’t really know but who feels, in some way, like a sister. In the way that grief upends your life and sets you on courses you never imagined, puts you in orbit around other, distant stars.

I feel like my life was going one way up until Jess died, I told my friends in Wales. And then after she died it took off in an entirely different direction.

That direction was dark and hopeless for a long time. It wasn’t a billion years, but still, it felt like forever.

And yet. Even a billion years—even 13.8 billion years—is not forever.

It’s tempting, isn’t it, to find ways to fit the data around the world. To say well, we’ve established that the Big Bang happened 13.8 billion years ago, so there must be something in that far-off light of these so-called old galaxies that we’re not seeing. Some miscalculation, somewhere we’ve gone wrong. We strive so hard to find ways for things to make sense. And yet the entirety of human progress has been the process of letting go of what was once accepted fact. Galileo thought that Saturn “had handles” because his telescope was not yet advanced enough to discern the planet’s rings. We used to think that electrons orbited the centre of a nucleus, like planets. But now we know that this isn’t entirely true.

We are always learning, which means we are always letting go. You cannot hang on to anything forever.

In the first months after Jess died I felt so hollow it sometimes felt surprising to know that I was still alive—still breathing, still doing, still going through the motions. Gobsmacked to know that somehow things still worked. You could breathe and eat and sometimes even smile, even laugh. As the months went on and my orbit carried me farther and farther away from that life I’d known with Jess, the winking into life of other stars felt almost infinitesimal. But still, slowly, it happened. One bit of light and then another—a year later, two years later, more. And now I am coming up to the four-year anniversary of Jess being gone and it is like seeing galaxies all around me where for so long I’d assumed there was nothing. The world and the universe all around me alive with wonder in a way that I thought I’d understood before but now, somehow, understand even more.

And at any moment—any moment—another universe-breaker could drop into my life and smash it all to bits, plunge me right into the dark again. In much the same way that life is now reeling and spinning again for these friends of mine who are each, separately, staring down the gaping maw of loss. How miraculous and cruel our universe is. How beautiful. How awful. How staggeringly unfair that love in all its perfect beauty can visit us only to then be taken away. How do you hold all of that? How do you make sense of it all?

You don’t, is what I’m finally discovering. Some things never make sense. Or they make sense in a way that is so small in the face of the universe—like figuring out exactly how old a galaxy 13 billion years away might be—so as to mean almost nothing. (And everything, at the same time.) We live and love and hold great gifts so close in our time here on this tiny planet. We rage, and we despair. And we do all of this under the winking light from stars so far away it’s almost impossible to fathom. Inconceivables in one hand, inconceivables in another.

We’re small in the face of all of it, we tiny human beings. And yet we reach so far.

The 3am anxieties haven’t gone away. I have been back in Canada for a week now and I still find the winter ahead faintly terrifying. What a monstrous task this book is going to be! But like grief, there is only one way through it. Moment by moment. Step by step. Slow, careful breaths.

When I was on the Isle of Skye I went into a kitschy little gift shop. There is a story attached to another gift shop on that island that I will share, and soon. In this particular instance, I went into the shop and saw this quote on a little plate:

When it rains, look for rainbows. When it’s dark, look for stars.

The Internet tells me that this might be the work of Oscar Wilde, or it might not. I love it either way. Because the whole business of grieving is exactly that—looking up into the dark sky above you and searching for light, even when the dark seems to press down and say: there is nothing here anymore.

Eventually, the longer you look, the more stars you’ll find. And one day you’ll discover that those stars strung out in the vast night sky above you have been there for so long they are entire galaxies. Lighting the way forward even when you thought that wasn’t possible, until eventually this new understanding becomes another thing to hold.

Currently Reading: The Smallest Lights in the Universe, by Sara Seager

Currently Watching: Life On Our Planet

Currently Eating: This Chili Lime Tofu Manchurian. 15/10, highly recommend!

So beautifully, thoughtfully written, as always. I was standing outside in the middle of Vermont earlier this week, looking at the sky, where the skies are darker and the stars are brighter. Grief has been that way for me--so dark that it made the light more visible. ❤️ Sending light to your friends who are in those early days of darkness.