The Sunday Letter #15: Live, live, live

In the immediate days after Jess died, I remember walking around filled with a horrible kind of dread. It was a dread borne out of knowing that she was gone and I was still here, and could be here for years. I could live until I’m a hundred and one, I remember thinking one day, blinking at the island in my kitchen as I tried to make myself a coffee. How am I supposed to get through all of that time without her? How can I bear a life so long and empty?

The day after I found out I sat in my friend Catherine’s kitchen and said the same thing. “My life feels so long,” I told her, and I felt at once grateful for this knowledge and also like a traitor. How do I do another year like this now, never mind forty? How do you keep going when this thing that feels like it made your life worthwhile is all of a sudden gone?

“I know,” Catherine said. “It is. It will be. There’s no way around it—you just have to go through.”

As the days passed, each one so hard and yet, imperceptibly, the tiniest fraction of a little bit lighter—hello darkness, my old friend, I recognize you now, have some space on this bench even though I don’t want you to stay—a new fear came up to sit with this first one.

I hate the thought of going on, I wrote to Jess’s sister. I hate the thought of my life moving forward in any kind of way that doesn’t have Jess in it. How am I going to feel a year from now, or two, or three? How can you do things—fall in love, go on a trip, publish a book? What if I have kids in the future who’ll never get to meet her? How can any of us exist in a world where she fades into the past?

What I didn’t say in those emails, because I couldn’t find the words for it, was this: How do you not only get used to existing in this new universe without someone but also find that you’re enjoying yourself while you do it? How will I be able to stomach those moments, when they come?

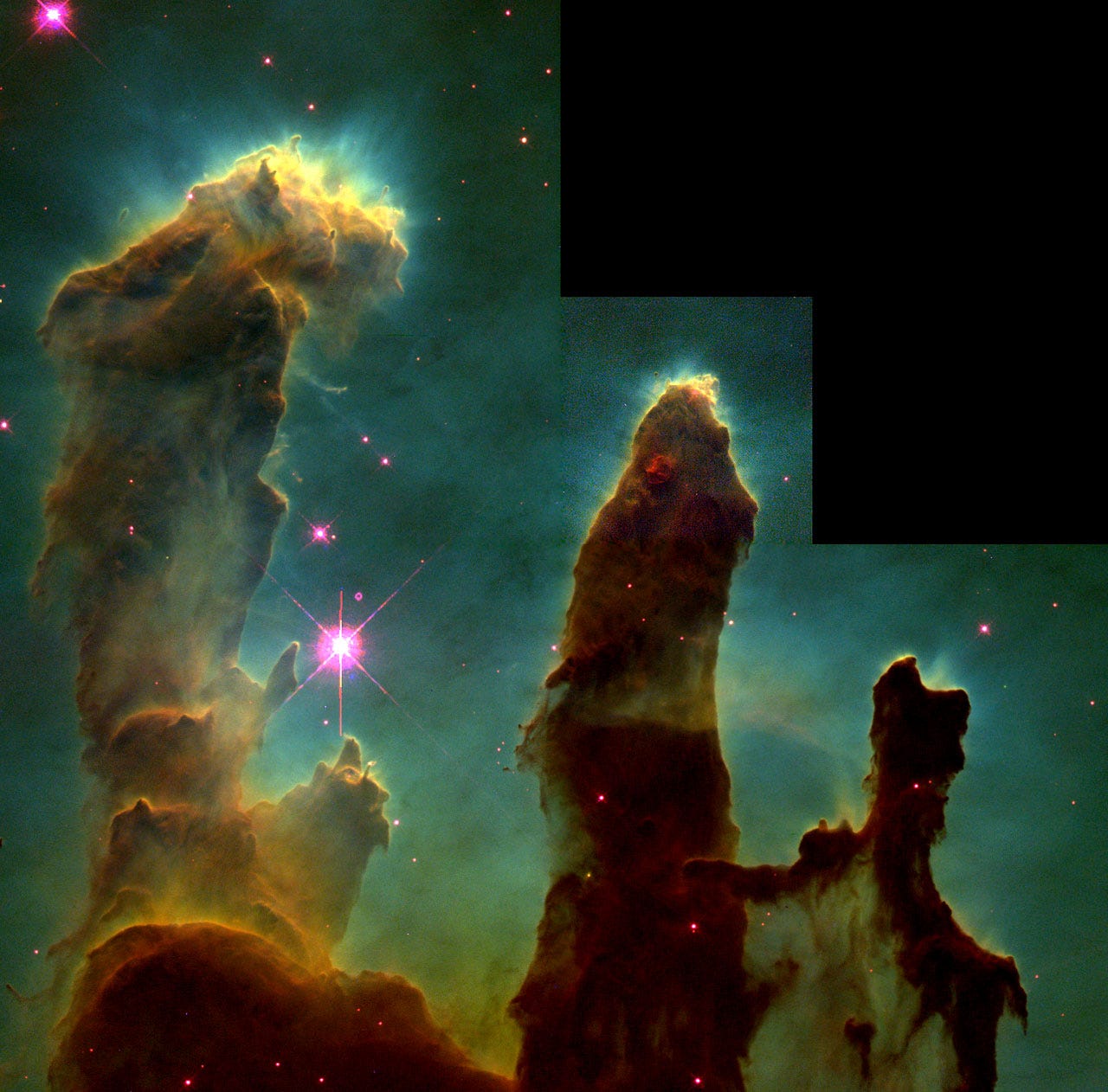

The Hubble Telescope, launched in April 1990, has been sending us beautiful photos of the cosmos for the better part of the last three decades. The first photo of the Pillars of Creation came in 1995, followed by an updated, wider version of the photo in 2014.

The new photo from the James Webb Space Telescope shows the same pillars in an even more diaphonous state. What was murky before is a little clearer, a little brighter; what was obscured in 2014 can now be seen—or seen through—quite clearly thanks to the JWST’s enhanced technologes.

I don’t pretend to know how any of this works—how the telescopes collect data, how they can see so far into space (I know, I know, it’s a matter of lenses and magnification—I still don’t understand it fully! Mathematics might as well be sorcery, as far as I’m concerned!), how infrared vs. visible light can illuminate so many things we haven’t yet discovered.

Instead I find myself thinking things like this: do the Pillars of Light have an actual name? What would inhabitants of the Eagle Nebula say if we were to travel all 7,500 light years to their doorstep and proudly announce our arrival? “We have arrived at the Eagle Nebula! Hurray us!”

“Eagle Nebula?” they might ask. “What’s an eagle?”

Last week, as I walked through a park in Cardiff and caught up with old friends, I found myself thinking about those early, raw days of a Jess-less universe. I held the thought of her as I stood beside my friend and his son and waited for fresh donuts from an Italian food truck. I thought of her as I stood there suffused with happiness, a perfect kind of contentment stilling through my veins. It didn’t rumble, this contentment. It didn’t announce itself with noise or excitement or anything else. It was just, suddenly, there. There I was, on an overcast day in a Cardiff park, talking about Manitoba wheat and Italian flour made in Puglia, smelling fried dough as it cooked, waiting patiently for those delicious donuts and feeling so thankful to be there with my friends, to be in Cardiff at all, to have a walk around the lake ahead of us and a few days more ahead of quiet time and laughter.

And the grief, it was there the whole time. This is so lovely, this is perfect and my life will never be the same right there, hand in hand. And it was…entirely doable. Entirely manageable. Like being forced to welcome some kind of prickly, terrifying pet into your life, one that you have to bring everywhere with you and then, somehow, gradually come to tolerate and perhaps even to love.

We are going to Cardiff today, I might have said to my grief-pet. Calmly and gently, as though it was the most normal thing in the world. Next week, we’re going to the Isle of Coll to look at the stars. I didn’t feel bad, or guilty, about any of it. Life was going on and I was eating my way through it and trying to keep my heart open to wonder just as Jess would have done had she been there right beside me in the flesh.

Here—have a donut. It’s very good. Jess would absolutely have loved one, had she been here.

One of the things I’ve discovered over these past few years is that I can’t pretend to understand how grief works either, even as I continue to barrel my way through it. Saying that I understand grief now that I’ve had this up-close-and-personal experience of it feels a bit facetious, kind of like how I imagine it is to say that we understand and can name elements of our universe even from seven-thousand light-years away. We understand—or think we understand!—what we can see, but as the example of the Pillars of Creation photos show, what we see can also always be evolving. What was murky can eventually be shown to be clearer than we thought; the difficult, murky process of grief can also come clearer over time. The prickly nature of that terrifying pet becomes something that you can also make space for. Yes, you. Here you are. Have a seat—there’s as much room as you need.

How is it possible to have and hold all of these things at the same time? I don’t know how. but it is. I still hate the thought of moving forward through life without Jess—of making discoveries and doing new things and enjoying the world without her physically here. Moving farther and farther away from her memory every year. And yet here I am, doing these things anyway. I hate the thought of being here in Scotland without her, and yet actually being here, in Scotland, even without her, is really lovely. I hate the thought of taking joy in being with old friends and celebrating the triumphs and the milestones of their lives all while knowing that Jess won’t get to have her own triumphs in the same way. And yet here I am, taking that joy anyway. Being content. Being happy, when I wondered for such a long time whether happiness would ever be possible again.

In April of this year I sat around a dinner table with Jess’s family, all of us trading stories about this beloved woman we all miss so terribly, and we laughed and laughed and at one point I thought, I can’t hold this laughter and this sadness all at the same time, I just can’t. It felt like indigestion of the heart—a simmering bubble of something right there in the middle of my ribcage, uncomfortable and raw. And yet at the very moment I said this to myself—I can’t, I can’t, not anymore please, I can’t—I did, and continued doing, and that uncomfortable heart-indigestion sat down right there on my bench, beside my prickly grief pet, and I blinked and looked at both of them and though, well, okay, here we are then. All of us together.

Amazing, isn’t it, how your soul holds so much.

I worry often about whether I’m being unfair in writing about Jess—in taking this year off to write, to focus on this friendship and this friend in particular, in ruminating again and again on how extraordinary our friendship felt, how special she was and is to me. It’s a sliver of the same kind of worry that took up residence soon after she died—the worry and recognition that grief makes you live in a different universe, makes you chart a different course from the one that you’d imagined yourself living. How can I continue to be fair to all of my other friends from this side of the universe where grief has thrust me?

I feel like my life was going one way up until she died, I told my friends in Cardiff last weekend, marking the path on the table with my arms, and then after she died it just took off in an entirely different direction.

In truth, I had worried that it would feel strange to see them, these people I hadn’t seen in a decade. Would we have the same things to talk about? Would I appear flighty and frivolous and somehow immature, given that they were now parents? Or would our collective life experiences have shoved us so completely on opposite sides of the galaxy that looking at one another would be like looking through the gas pillars in that old Pillars of Creation photo and trying to determine what lay beyond them? Who knew?

And yet when I saw them both and arrived in their house it was like time had collapsed entirely. A wormhole back to our days in Edinburgh in 2010—only better, because it was present me and present R and N slipping back into our old patterns, rich with our decade of collective experience and new ways of seeing. They have two beautiful children now, and a house just outside the city. She has a garden and is working as an illustrator and he has a studio in the backyard for his film editing work. They are every bit the people I knew a decade ago, and also more, contining to grow in ways that I am hopefully also growing. And we’ve managed to watch the same TV shows and many of the same films on opposite sides of the Atlantic even in these years of being apart.

Turns out the connections to your old life don’t go away even when you’re barrelling outward into the galaxy, feeling the tether grow fainter and fainter with each passing year. Turns out that as you move forward you also expand, so that you’re holding—or can choose to hold, if you want—the past and the present at the same time.

I stood beside that food truck and waited for our donuts, and I enjoyed every delicious minute of it, even before the donuts arrived. The way that I’ve been trying to enjoy every delicious minute of this trip—this wondrous, incredible trip that has been made of so many mundane, ordinary moments. (Like how a grant application is one long, onerous—one might even say odious!—task that can transform into radiant possibility.) I haven’t felt guilty and it hasn’t felt awful. Even as I can continue to acknowledge that the reality of life—living it without Jess, and continuing to do so for however long is required—continues to be awful in some way. It is still, somehow, glorious.

A little voice has been whispering in my ear as I’ve made my way through these Scotland days.

Live, live, live, the little voice says.

Live, live, live. Eat the donuts from the food truck. Go chase old memories across the ocean. See old friends, make some new ones. Publish another book. Write another and another. Spend whole days ensconced in your St. Andrews cottage and bingewatch the latest season of The Wheel of Time, if you feel like it. (Thanks to the weather and a stomach bug for making that little bit of rest and recovery possible.)

In those first days and months of grief, everything felt obscured and murky. No telling what, if anything, waited on the other side—or if there was an other side at all.

In February of 2020, just before the world shut down, I went to New York City and gave my first (and as it turned out, only) in-person reading of Disfigured. Before the reading I went for dinner with my dear friend Mira Jacob, and as we sat over our margaritas I said it, point-blank.

Does it end, I said. This feeling that you’ll never be happy again?

Yes, she said. Simply and honestly, the way that a griefwalker knows. Yes. It will.

And now here we are, almost four years later. The grief does not end, but somehow happiness comes back to sit on that bench, and somehow there’s room for everyone to be here.

The gas and the clouds do not disappear, but what you’ve learned in the intervening years allows you to see them differently, to see the world through and with and alongside those stellar clusters.

You might even say that the grief itself allows you to see the gas and the clouds and the entire universe around you in a different, more magical way. One that would not have been possible otherwise. To expand your love into something you didn’t know was possible, to explode it into a light that maybe, just maybe, can be seen from seven thousand light-years away.

It feels strange to be grateful for this, and I would turn around and give it all back in a snap just to have her back, as Cheryl Strayed has said before.

But. Like Cheryl has also said: my grief is tremendous but my love is bigger.

Live, live, live says the voice.

Live. Live. Live.

I suppose it could also be saying this: love, love, love.

Love. Love. Love.

And so I do, and so I will.

Currently Reading: this newsletter, over and over, because I want to get it right. :/

Currently Watching: Season One of Upload.

Currently Eating: coconut shortbread from Duncan’s of Deeside. Want my shortbread review? Of course you do! Follow along as I review the entire* oeuvre of Scottish shortbread, biscuit tin by biscuit tin**, here.

*slight exaggeration, obviously

**or biscuit box, as the case may be