I recently had the chance to do a guest post over on The Clearing, the wonderful newsletter run by the extraordinary Katherine May. Please check it out, if you haven’t already!

I am forty-two years old today. 42! It is, as you may know, the answer to (life, the universe and) everything, according to Douglas Adams.

From this vantage point (sample size: one human being), I have to say: things feel pretty great. Several weekends ago I was playing this game with my nieces and we came upon a trivia question that asked you what age you really liked in your own life, and all I could think was: now. I really like now. I like who I am so much. The forties are EVERYTHING.

The journey to get here? It has been…well I suppose it has been everything too, in a different way. I have been privileged and lucky and the recipient of so many bits of good fortune over the course of my forty-two years on this spinning rock of ours. I have been abundantly loved.

But I’ve also worked hard to get here, and been through a heck of a lot. My twenties and thirties held some very dark times. And while I know that I would never want to go back there, I can’t help but view even those difficulties through a different lens now. Being able to view aging through the lens of impermanence and growth has been life-changing. I am grateful for it all.

Happy birthday to me.

In last week’s Stellar Survey I posted a link to a Vox.com story that talked about the ninety-six (96!!!) bags of urine and feces and other detritus that the Apollo astronauts left on the moon over their subsequent landings. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about that story ever since. It boggles my mind, mostly in that it feels both horrifying and inevitable: oh my goodness, I can’t believe we left our trash on the moon and but of course, why wouldn’t we do that, isn’t that just our MO?

It feels at once extraordinarily hopeful and also extraordinarily depressing: look at the photo below. That’s the first photo—the first photo—Neil Armstrong took after he landed on the moon. And what’s front and centre, apart from the legs of the moon lander and all of that grey moon dust? A white bag of trash (also known as a jettison, or jett bag).

Good night, Moon. Humans have arrived and now everything will be different.

I think I keep coming back to it because it feels like a perfect metaphor for being human in the world these days: great heights, yes, and also the greatest of lows.

I am working my way through what is turning out to be a difficult chapter in my memoir about Jess. It’s difficult in part because it’s about dark matter, something that the smartest people in the world have only the faintest understanding of. (I am so far from being the smartest person in the world that you could argue, quite convincingly, I have no business writing about dark matter at all.) But it’s also a chapter about grief, and I know a little more about that than I would like, and so here I am, writing about both of these things in a chapter that may or may not be a success. Jury’s still out.

In the chapter I talk about how the last time I saw Jess in person was at her wedding in 2016. That was a difficult few days for me, as much as it was also a wonderful time. It was difficult because I was jealous of the fact that Jess was getting married and I hated myself for being jealous. I had wanted badly to be her maid of honour and I wasn’t, and I was hurt and also angry at myself for being hurt in the first place (we’d never talked about standing up for each other in this way, and to hang on to an expectation of something we’d never even discussed was unfair, and I knew this at the time, and still I felt it!). I was angry at myself for being so petty and ridiculous, for being so afraid, after nine years of a perfect, soulmate friendship, that something like marriage was going to take her away. I hated myself that weekend, as much as I was also so happy for Jess. Because I was happy for her—indescribably so. She was so radiant, and so kind, and so present in ways that felt nothing short of miraculous. (I mean—weddings gonna wedding, right?) I was excited for her, and for what this new stage of her life would bring, and absolutely convinced that bright and beautiful things were ahead—and also I was sad and lonely and jealous and scared. The fact that I could hold both of these things inside of me at once—the joy and the jealousy, the love and the everything-else—felt impossible and also, somehow, boring. Like I was choosing to throw a bag of trash onto the ground after having achieved some pinnacle of human progress.

I feel like I fell short that day. And when you are grieving, those are the moments that you circle back to, over and over. The instances when you were not enough, even if that wasn’t evident at the time and even if things go back to their usual blissful rhythms after those falling-short moments.

I should have been better, I kept saying to myself in all the years that followed. That wedding day was the last time I saw Jess alive. I flew back to Canada after the weekend was over and a few months after that she got diagnosed, and then life became Skype calls and phone calls and texts and promises that we would see each other soon, that we would catch up and go travelling again as soon as her treatments ended, we would, we would, we would. And also, I love you I love you I love you, over and over. We said that to each other all of the time.

Rationally, I know that what transpired on that wedding weekend wasn’t actually all that terrible. I Had Feelings, but I kept them to myself. I was being short-sighted and petty but I knew, even then, that the pettiness was not the whole of who I was, that everything would soften with time. We loved each other fiercely and would go on doing so right up until the moment that she died—and after. All of that was and is true.

But man—writing about it? Going back to the Amanda-that-was and delving into Those Feelings all over (and over, and over) again? Dredging up my shortcomings as a friend and asking myself: maybe she deserved so much more than you? Leaving the naked, puny truth of my small humanness out there for the reader even as I grapple every day with that aching, abysmal grief of knowing she’s not here, not in the way that I want her to be?

Not for the faint of heart. That’s for sure.

There were, as it happened, legitimate reasons for jettisoning all of those bags onto the moon back when Apollo was doing its thing. One of the most salient reasons has to do with weight. When you’re an astronaut going to the moon on a scientific mission, you have orders to bring back things to study—moon rocks, moon dust, etcetera. All of those things add weight to your spacecraft, which means that if you don’t get rid of something on your return trip home, you’ll be flying back to Earth in a ship that is heavier than it was when you left. And this can affect many things, chief among them the angle of entry and the propensity for exploding in the atmosphere. As noted by Andrew Shuerger, the space life scientist quoted in the Vox article I linked to above, “the Moon missions were engineered very carefully, and weight was a very big issue…[S]o it made sense if you’re picking up moon rocks, you’d also want to discard things that were not necessary to increase your margin of safety.”

All of which makes complete sense. But it doesn’t negate the fact that the Western colonial mindset was alive and well (I know: has it ever died?) when we went to the Moon: we’re going to go because we can, and we’ll discard whatever we need to along the way. It’s that kind of thinking that has led to our current space junk problem, a problem that shows no signs of going away. Humans gonna human at the end of the day, as we now know all too well. (See also: the trash on Mount Everest.)

But that doesn’t mean we have to be this way forever. As necessary-at-the-time-and-also-questionable as the trash bag on the Moon problem was and is, it will also yield some interesting scientific discoveries. When we head back to the Moon in the latter part of this decade, the plan will be to retrieve the trash bags and see if any bacteria survived in all of that poop. (Poop is full of bacteria. The building blocks of life!) Thanks to the Moon’s lack of an atmosphere, the chances of survival are probably quite small. But Apollo astronauts also kept nine different species of microbes on the outside of the spacecraft for several days whilst on the Moon, and they survived. We’ve also found bacteria and other microbes in incredibly harsh conditions on our own planet, conditions hitherto thought to be inhospitable to any kind of life.

So it’s possible that something might have survived. Even if it isn’t probable.

The growing awareness of our impact on everything around us—along with the awareness of the world’s impact on us—in the intervening decades has also shifted the conversation on a larger scale. NASA hopes to retrieve those trash bags and find ways of recycling other garbage that will inevitably get created during future moon missions. We are beginning to ask more of the right questions when it comes to environmental considerations in space, and to understand how actions from long ago can have far-reaching consequences.

We are capable of it all, in other words. Great feats like landing on the moon and low points like throwing trash on said moon and climbing-back-up moments of trying to envision a new and better way to be.

One of my (many) worries in writing this book is about the abundance of metaphors that space exploration throws up for grief. Because grief is like reckoning with the trash bags that you threw out of your Apollo lander decades ago, and grief is also like the orbit of a planet around its chosen star, and grief is also like dark matter, or like the patterns we see in the sky.

Pick one metaphor and stick to it! I imagine my editor saying. Otherwise you’re going to risk your reader becoming confused!

But what is life, I wonder, if not confusing? What is life like, if not…everything? It is like everything because it is, in fact, everything. Everything that we are is a part of everything else in some way.

Thich Nhat Hanh called this interbeing. We inter-are, he said. You inter-exist with everything else: the sun and the moon and the stars and the yogurt that you had for breakfast. You cannot be you independently of any of these things.

And so I am finding: I cannot be me independently of this grief. Because I cannot be me without her, much as I cannot be me without anyone else. (Especially you, reading this newsletter, right now.)

We cannot be us without the space trash that has been left on the Moon, in other words. Mistake or not, it has brought us all to this point. Future moon missions and landings and recycling plans and the acknowledgment that if we head to other planets we should probably be very careful and maybe, somehow, we can reach for a world (ours!) that is better.

All of it is, because of everything else.

Two years ago, when I turned forty, I wrote about the surprise sense of delight that descended into life when I turned thirty-nine. That last year of my thirties—a time I’d imagined was going to be so fraught and filled with stress—instead relaxed into something else as the days went by. A stronger sense of who I was and what I wanted. A soft, flowing-with-the-current trajectory that saw me wake up on my fortieth birthday with the simplest of realizations: I actually liked myself.

I really, really liked me. I liked how I thought and what I did in the world and what my dreams were. Such astonishment! Such surprise! To wake up in the morning and discover this sudden and most simple of gifts, as though I’d come face-to-face with my tiny child self and recognized her all over again.

You. It has always been you.

On that day of Jess’s wedding in 2016, I was afraid that married life would take my best friend away because I didn’t like myself. And so it seemed logical that married life for Jess would do exactly that. Why bothering sticking around with someone like me when life in love was so much more exciting?

What does it feel like, to look back on your life and realize that all of those times when you worried that people didn’t like you or were going to leave you in some way were actually just moments of you not liking yourself and who you were?

What does it feel like to then wake up and discover that love for yourself at forty, along with a soft, expansive state of grace that keeps unrolling further with every year that speeds on by? To wake up at forty-one and now forty-two and think: I love this age, I love right now, I feel surrounded by gifts even in the midst of grief.

Even the grief. All of it intertwined with everything else. Because of course Jess—as did many other people—loved me exactly that much. Even before I could do it myself.

Who would I be, if not for her?

Who would I be, if not for you?

And so here I am, in the first early hours of forty-two years of age. Life is wonderful and terrifying and awful and strange and glorious even in its most terrible moments, and to love it is to love the cosmic expanse of space.

I am smack in the start of a new age of creative excitement and financial insecurity and I have no idea—no idea—what the coming months will bring. (Feeling generous and in the mood for a birthday gift? Please consider a paid subscription!) I’ve spent the last three decades of my life methodically planning everything out, the way that all of those scientists at NASA calculated the weight on Apollo down to the gram. Does catastrophe await? Maybe!

Or maybe everything that is happening now is happening because all of those decades of striving and uncertainty and fear and despair—and all of the joys and the grief that went with them. As it turns out, that’s a calculation of its own too—a realization that you can carry and have space for all the things.

The forties have been good to me, so far. But that’s because I have been good to me, at long last.

What a gift, truly.

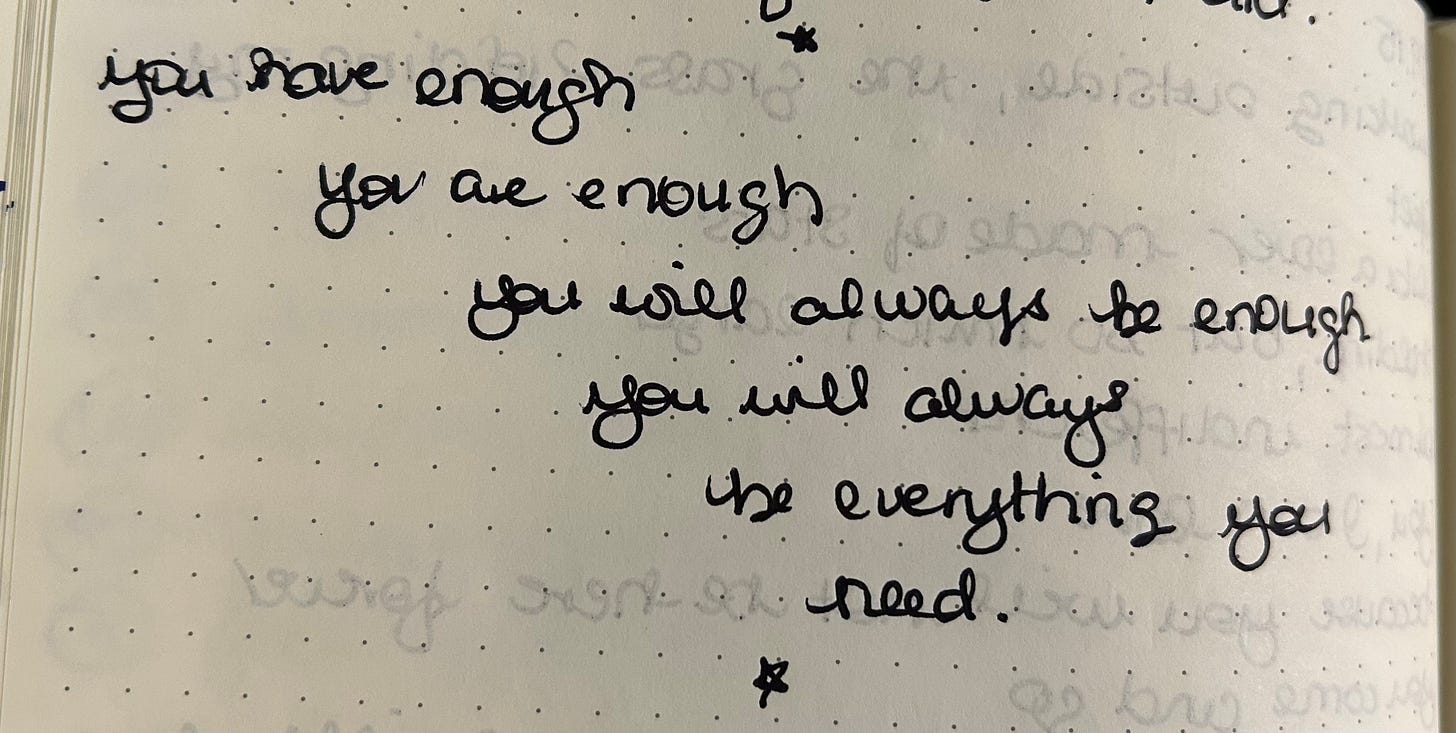

When I was at the fall retreat at the EIAB last September, I wrote a few poems. I wrote them quickly, in the early mornings, as we sat at dharma talks. Thoughts and feelings swirling down onto the page. They are not great poems because I am not really a poet at all, never mind a great one. (Oh, one could wish.)

But I wrote one that I keep coming back to, as a reminder. My own little mantra as I make my way through however many years I have left.

It feels like a good gift to re-open as I spin into another year of my forties. I hope it can be a gift for you too. Happy birthday to you, wherever and whenever this may find you. May these birthday wishes follow you throughout the year and ping you whenever you need.

May we be happy.

May we be safe.

May we all move forward into life knowing that we have everything we need to meet it.

Most importantly: may this day, and all days following, bring you so many opportunities to love yourself, and who you are.

I want that for you with my whole heart.

And so too, somewhere, does Jess.

Thank you. I read this and it was so beautiful that it made me cry.

Happy belated birthday! This is just absolutely beautiful!