Shortly before the cosmic inflation that followed the Big Bang, the universe entered what is known as the Planck Era. (I say “shortly before”. What physicists say is several picoseconds before the cosmic expansion. One picosecond is equivalent to one trillionth of a second. One picosecond is to a second as one second is to 31,689 years, or so says Wikipedia. The scale of this is at once so large and so vanishingly small that it might as well be meaningless to me.)

The Planck Era is named after Max Planck, the German theoretical physicist who is famous for discovering the Planck length, which is the smallest measurement of energy we have. We don’t know much about this period of time, because travelling so far back into history brings us to a moment—a singularity—where all of the rules of physics break down and time and space themselves become meaningless. General relativity tells us it is possible that this singularity was held in balance, with the four physical forces—gravitation, electromagnetism, strong and weak interactions—in such unimaginable symmetry that physicists have compared it to a sharpened pencil perfectly balanced on its point.

Too good to be true for too long, and so.

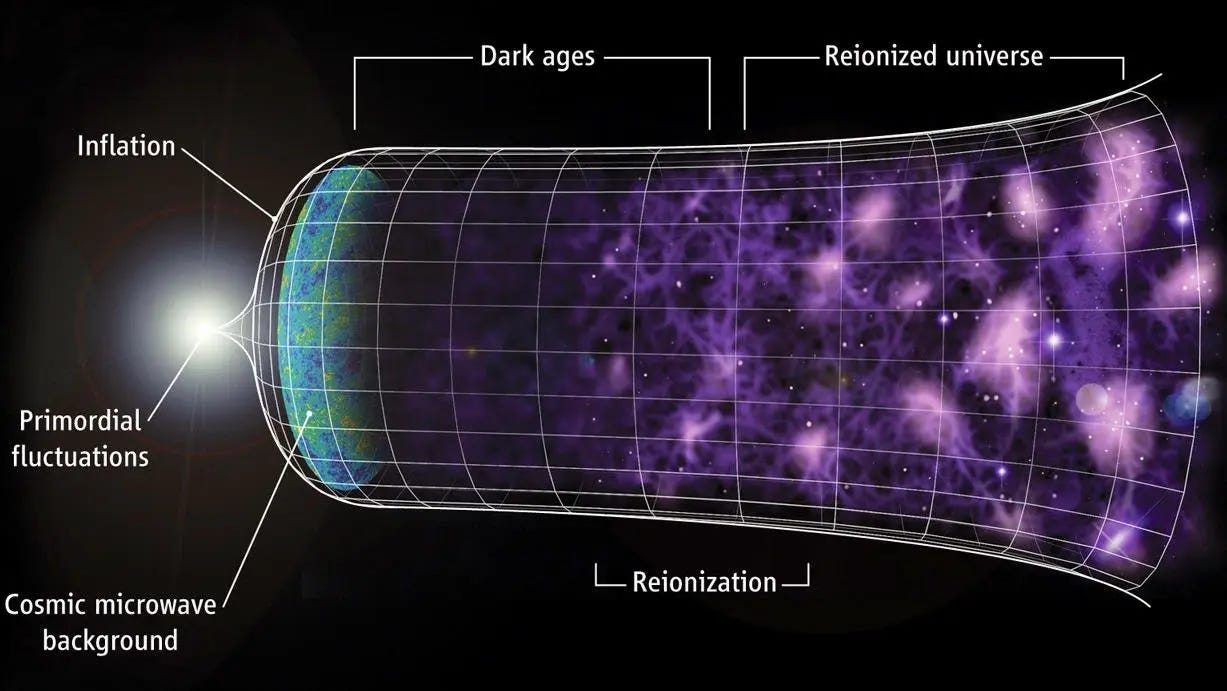

1) Explosion, and then

2) Planck Era, the primordial soup, and then

3) Grand Unification, where gravity separates from the other forces and the earliest elementary particles and antiparticles are created and then destroyed instantly again and again, the universe too hot to allow them to continue, and then

4) Inflationary Era, or Cosmic Inflation, and then

5) Electroweak Era, where the strong nuclear force makes like gravity and separates from the remaining two forces, allowing for further universe cooling and the emergence of special particles like W and Z bosons and the Higgs boson, and then

6) Quark Era, when quarks—one of our first elementary particles—begin to form, and then

7) Hadron Era, when the universe cools enough to allow quarks to combine into hadron and anti-hadron particles, and then

8) Lepton Era, from roughly one second to three minutes or so after the Big Bang, where the hadrons and anti-hadrons from the previous era have mostly annihilated themselves and allowed for leptons and anti-leptons—such as electrons and positrons—to arise and collide into one another, releasing energy, via photons, into the void, and then

9) Big Bang Nucleosynthesis, where the universe cools enough for atomic nuclei to form, and then

10) Photon Era, from roughly three minutes after the Big Bang to 240,000 years after the Big Bang, where the universe is filled with hot, but cooling, plasma, and then

11) Recombination Era, from 240,000 years to roughly 300,000 years after the Big Bang, when the universe cools to about 3,000 degrees and allows for electrons to bind to atoms, releasing photons across the vast space of all that is, and then

12) Dark Era, from 300,000 years to roughly 150 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe is a large mass of photons and neutral hydrogen atoms and dark matter, mysterious and inscrutable, without even light to lead the way.

Imagine that: the universe, filled with nothing you can see and so many things that you can’t. A velvet cape of darkness that extends farther than you can fathom, at once empty of all that you know and filled with so much more possibility than you can wrap your head around. Everything that will become you and all those that you love is in here, dormant, waiting. A trickster veil, a blink of time lying in wait.

I imagine it must have felt like forever, that darkness. Endless and lonely and bleak. The hydrogen clouds that dominated the space absorbed most of the ultraviolet light that came from those tiny photons, so for long, long stretches of time, light was just something that grew at an infinitesimal pace. Swallowed by the larger dark. Like trying to light a candle in a room without oxygen.

It could be a horror movie, couldn’t it. No light no matter where you turn.

I am interested in the Dark Era, or the Dark Epoch, or the Cosmic Dark Age, as it is variously known, as it relates to space but also, of course, as it relates to grief.

I’m also interested in it right this very moment because coming back to Substack after what feels like an interminable amount of time away (but isn’t, really, in the grand scheme of things) kind of feels like emerging from some dark other place. Not dark as in sad or scary or anything of that nature. Just dark as in…creative dark?

I’m interested in this period of time, this from-300,000-years-to-150-million-years-after-the-Big-Bang or so, because there’s so much of nothing and also everything that happens in there. Which is also what happens in the creative dark. All of that time that you spend just sitting and thinking and trying words out on the page and sometimes just trying words out in your head for a long while to see how they fit. Waiting for something to speak to you, for something to ignite.

Most of the past year has felt this way. I took a year’s leave of absence from work back in July of 2023 to focus on a new project, one that was inextricably bound up in grief and the cosmos and needed, I felt, a long stretch of time away where I could do nothing. A long stretch of time where I could just travel back to old memories and travel forward into new ones and spend some time letting the universe speak to me in whatever way it needed.

It feels strange to look now at this year from this point of almost-in-the-future. Ten months have gone by, already. I go back to work at the beginning of August.

I had so many Big Plans for this year. And so many of them have come to pass, and still part of me feels like so much of the year was spent being quiet, being still, and waiting.

Everything has played out exactly as it needed to. I feel this in my bones.

Gradually, as the universe continued to expand and cool during this period of time, these 300,000 - 150 million years after the Big Bang, the denser clouds of hydrogen began to collapse in on themselves and form stars. (Remember: the more matter you have, the greater the warping—in this case, great enough to warp the fabric of spacetime around the birth of a sun or two or three.) And as the photons produced in the nuclear reactions of those stars moved out in to the universe, more stars were born and fell together into galaxies.

For a long time, because neutral hydrogen was so plentiful in this early universe and the stars and the galaxies were comparatively so few, the hydrogen gobbled up any light that the stars and galaxies produced. Then those early stars and galaxies eventually died and exploded out into the universe, seeding other stars and galaxies. The remaining hydrogen clouds around these galaxies, if they didn’t collapse into stars themselves, became more diffuse thanks to the universe’s continued expansion, and gradually the stars and galaxies became more and more and as spacetime stretched out the available hydrogen became less and less, until the amount of light that these galaxies produced was enough to reionize all of the neutral hydrogen in space.

Suddenly but not suddenly, over hundreds of millions of years, there was light where there had seemed to be none before.

I have Substack news. Or perhaps not so much news as just a little update, which is that I am removing the paywall from future posts and making everything free here, at least for the time being.

I’m doing this in part because these last few months were mired in illness (the Cold From Hell! It would not go away!) and I was so tired for most of it that I couldn’t post regularly, and sometimes I felt so guilty about this I almost couldn’t stand it.

I shouldn’t feel guilty. I know that. But I can’t and couldn’t help it.

Sometimes (most of the time) I find it difficult to square writing and money. I want to be paid for my writing. Of course I do! What’s more: I’d like to be paid a living wage for my writing, in a way that allows me to do nothing else but this all day long. (Spoiler alert: I don’t want to go back to work, as much as I like my job.)

But I cannot seem to fold myself into the mold of a content creator, and sometimes I feel like that’s what Substack wants us all to be. Committing to X number of posts for paid subscribers was a personal disaster because I immediately started thinking in terms of metrics: watching subscriber and follower counts, looking for numbers, trying to think about what would resonate and drive engagement, stressing in no small way about what to write and how to fulfill the promises I’d made to paying subscribers when what I really just wanted to do was write about whatever interested me and follow those interests wherever they went. And then I got sick and had to step back for a bit, and then the longer I stayed away the more I worried about those paying subscribers not getting “good value for their money” even though I was still following my interests and even though I know, for a fact, that my paying subscribers do not think this way.

Disaster, all of it.

And while I was recovering and working more intensely on this other project and thinking about this newsletter something started rolling in me, the way that I imagine those hydrogen clouds must have been doing all those billions of years ago. Cloaking the real work of the universe. Making it look like nothing was happening when in fact there were so many things happening all at once, all of it carrying you forward to here. And that thing rolling inside of me was this: I want this Substack to be a gift.

That is it. That is all.

So. For the time being, everything that I write here on Notes From a Small Planet will be freely available to all. The option to pay will still be there, but the Sunday Letters, the Stellar Surveys, the Constellation Ruminations, the personal posts, the random bits-of-whatever that occasionally show up in threads—everything will be free to read. I want to get back to writing this from a place of joy and curiosity and not from the worry around whether or not I’m taking advantage of my readers. (I don’t think this…mostly…but sometimes I do? Sometimes I worry so much about it! Capitalism is The Worst!)

Giving the work out freely—while still leaving the option to pay for it, if you so choose!—feels like the best way for me to do that. Another leap forward into a universe that I trust will take care of me, and of you.

Here’s the other part of the equation: I have News that will impact the frequency of these posts for the foreseeable future.

Notes From a Small Planet is going to be a book. Yay!

In February of 2020, Bahram Mobasher, a professor of astrophysics at the University of California Riverside, published a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters detailing a group of galaxies that had been sighted using information from the Cosmic DAWN (Cosmic Deep and Wide Narrowband) Survey. (The Cosmic DAWN Survey is a collection of data gathered from the Euclid survey, itself information gathered from the Euclid and Spitzer space telescopes, which undertook three separate Deep Field surveys—looking into dark, presumably empty areas of the sky to discover what lies in wait.)

Mobasher and his colleagues had observed the galaxies’ behaviour and deduced that they were in the process of reionization—turning the neutral hydrogen clouds around them into ionized hydrogen by knocking the electrons out of the hydrogen atoms and changing them so that they could no longer absorb light, thereby allowing the light from stars in these galaxies to escape into space. The galaxies, they discovered, were engaged in this process roughly 680 million years after the Big Bang.

In early 2024, new data gathered from the James Webb Space Telescope was able to pinpoint galaxies in the middle of this process existing even earlier—between 400-500 million years after the Big Bang. Most surprisingly, to many of the scientists involved in the research, these early galaxies were dwarf galaxies.

"We didn't think small galaxies would be so efficient at producing ionizing radiation,” said Hakim Atek, lead author on the research that detailed these findings. “It's four times higher than what we expected, even for normal-sized galaxies."

(Dwarf galaxies typically contain anywhere from one thousand up to several billion stars. The Milky Way, by contrast, has at least a hundred billion stars, so far as we can determine.)

As it turns out, some light was emitted during the cosmic dark ages because a hydrogen atom can only absorb light at particular wavelengths that correspond to the energy needed for its electron to jump from one level to the next. A photon with energy levels greater than that needed for the hydrogen to jump would have bypassed the hydrogen and shone. These small dwarf galaxies were filled with stars that shone just that brilliantly—the tiniest of engines, the most massive of outputs.

This is why the JWST, with its more sophisticated tools and capacities—tools capable of pinpointing those photons with those greater energy levels—has started to discover earlier galaxies than the ones previously established. But even the JWST won’t be able to pierce those earliest, thickest clouds of hydrogen. That job lies in wait for future telescopes and better technologies—or maybe it lies beyond the reach of even those.

The more we know, the more we see how much more there is to understand.

My new book, The Possible Universe, is going to look at my relationship with grief and the stars, and how all of this has unspooled in these years since Jess has been gone. I can’t share all that many more details about it yet, but I have an official contract and a proposed pub date of Spring 2026, and I am over the moon excited (teehee) about all of these things.

Of course, an official contract means that I now also have an official manuscript deadline, and that deadline is not, in the grand scheme of things, all that far away.

So. I’m going to be spending lots of time on my new book and I will probably have to get sporadic with these posts again. Or maybe I will post even more as a way of procrastinating! Who knows! The future is very exciting!

All of which is just to say: I am reminded, once again, that often when it feels like nothing is happening, that’s only because big somethings are happening on a level we can’t immediately see.

If you had told me, four years ago, that light would come into the sky again, I’d have been hard pressed to believe it. The darkness felt vast and untouchable, much the same way as that cosmic expanse of darkness must have seemed so all-encompassing all those billions of years ago.

But look: light was shining even then. Galaxies and stars and all of the matter that would eventually swirl into this blue planet of ours—it was there too. So many cosmic seeds being thrown across the universe.

Into my life, and into yours. Thank you to all readers old and new, and let’s see what blooms now in these days ahead.

Currently Reading: The Beauty of Falling, by Claudia de Rham

Currently Watching: Dark Matter

Currently Eating: This Edamame Crunch Salad

Currently Listening: To the dog, as she whines about going for a walk…

Fascinating post - I'll need to re-read it to click on all the era links to get a better understanding but you make it so interesting! Congratulations on your book - that is very exciting!

So excited about your book!